Travel

Jogjakarta, 2024

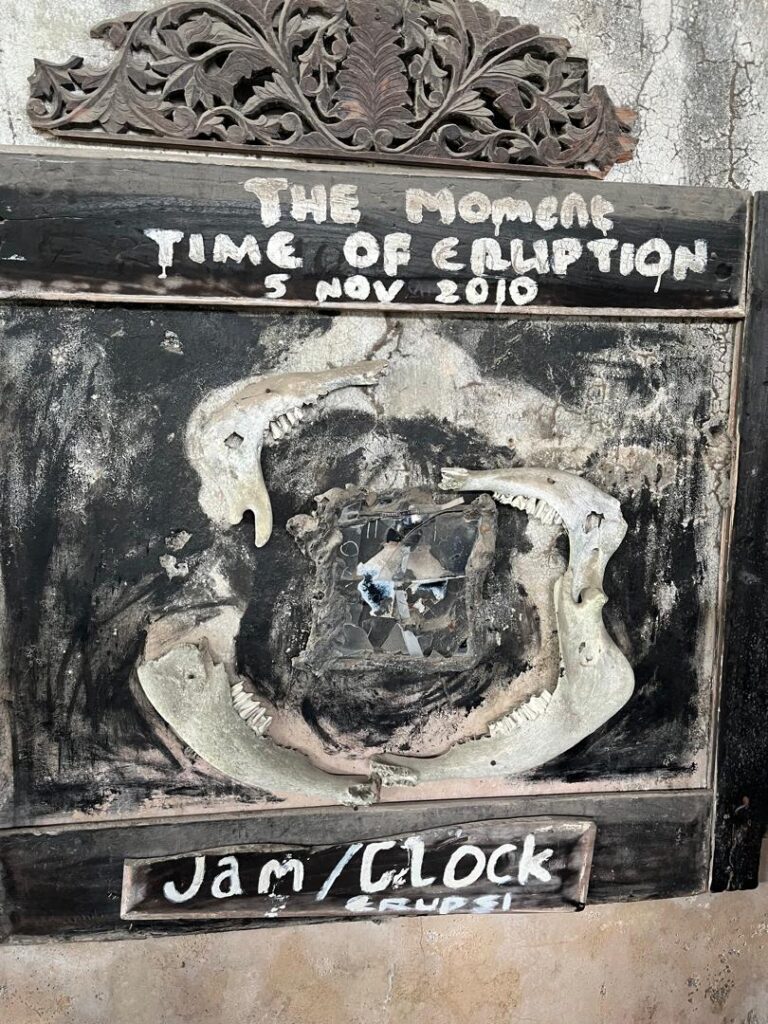

Jogjakarta, 26 October 2010. The clock struck 12.25 a.m., when the villages by the foot of Mount

Merapi were awashed by hot lava and smog that destroyed homes, livestock and human lives in one of the worst volcano eruptions in 200 years. Although most of the villagers were cordoned to safety weeks before the devastating incident, some insisted on staying on and were taken by surprise when the volcano flared up in the middle of their slumber. One such man was the Juru Kunci of Mount Merapi, Pak Marijan, who chose to stay on within the vicinity of Mount Merapi at the time. His last conversation with his son, Asihono, was vividly remembered and was also recorded. The recording of the said conversation is displayed in the Merapi museum, and continued to move visitors, where part of it goes as follows:,

Asihono: Saya minta pamit untuk turun mengunsi dan mengajak bapak ikut serta.

Mbah Marijan: Sudah, saya tidak usah mengunsi, saya mahu berdoa saja. Kalau saya ikut mengunsi nanti saya diketawain ayam.

Thus, Mbah Marijan, Juru Kunci or the keeper of Merapi, passed away in honor. Word has it that his

body wasn’t ruined by the volcanic lava, but villagers found his body intact in a position of prostration to God.

Such is one of the many myths and legends that surround the culture and beliefs of the city and people of Jogjakarta. What I found on my trip here this time was that God, nature and man are inextricably linked with one another and this is made evident in the rituals and events that are practiced in the everyday lives of the Javanese people. The three major religions that came and stayed with the Javanese people – Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam – made their unique imprints in the way of life of the Javanese people. The Javanese, according to my estimation, aren’t wholly Muslim, Hindu or Buddhist, but a people who revered the elements of nature including spirits and God.

The Borobudur has become an icon of Jogjakarta and it’s a must see on my visit here. A UNESCO heritage site, the Borobudur was built in the 8 th century, during the Buddhist Saleindra dynasty by Raja Samaratungga. Built with volcanic rocks of the nearby mountain, unconfirmed sources claimed that it took 100 years to erect the structure with elephants and men moving heavy volcanic rocks from the mountains. The Borobudur was a feat in human effort and ingenuity, with symbolic Buddhist elements instilled in the building. Finer details like the carvings on the walls depict the story of Life, Death and Karma of Buddhist teachings whilst the number of stupas constructed are highly symbolic of parts of Buddhism.

Another candi or temple that is a must visit is Prabanan. Candi Prabanan was built by Raja Rakai Pikatan of the Sanjaya Dynasty in the 9 th Century. Unlike the Borobudur, Prabanan is a Hindu temple, one of the most beautiful in the world. It is also built by volcanic rocks. The compound of Prabanan serves as historical evidence of tolerance having been long founded in Indonesia, with Hindu and Buddhist temples built side by side. Before the construction of Prabanan, there was a Buddhist temple built in the same compound called Candi Sewu.

In 1006, Mount Merapi could not contain its wrath and erupted once again. This time, the eruption was so severe that it almost destroyed the pride of the kingdom of that time – the temples of Jogjakarta – taking Borobudur, and Prabanan and its surrounding temples victim to its fury. The temples seem to have disappeared into oblivion; until centuries later when they were founded by colonial powers and been fully restored. Today, Borobudur remains to be one of the wonders of the world – evidence of past civilizations and an important proof of the historical tides that have given shape to the Javanese people.

Islam came to the Javanese islands, according to my guide, Wisnu, in the 11 th century. The Mataram kingdom at that time was one of the first Javanese kingdom to embrace Islam. The Javanese people, as is also evident today, are deeply rooted in the ancient beliefs prior to the arrival of Islam and maintained certain rituals that have foundations in Hinduism and animism. Islam was never spread forcibly or by the sword. The proponents of Islam in Indonesia, Wali Songo, spread Islam through art, culture and trade at around the 14 th century.

I was told that certain Javanese rituals, for example those that celebrate birth and life, are still actively practiced. Rituals like mitoni, brokahan and tedaksitan – to celebrate the important milestones of the child in the womb and its life – are not rooted in Islam, but are distinctively Javanese. There were also, as I was told, rituals involving incantations to the spirits, some pronounced in Quranic verses.

My trip to Jogjakarta was led by the question, “are Indonesians similar to Malaysian Malays, thus should be grouped as serumpun?” I’ll leave the thoughts to this persisting question to the reader, but as journeyed through Daerah Istimewa Jogyakarta during my trip, I find very stark differences not only between a Malaysian and Indonesian, but also between the Indonesians themselves. One cannot group together the Javanese with the Sunda or Sasak, and this leaves the question of serumpun much to be desired.

Finally, I was brought to Cepuri Parangkusomo, a historical building that links the earthly man with the spirits that lay beyond the physical plane. Inside the grounds lie two black stones known as “Watu Gilang” used by Raja Mataram summoned the spirit of the sea, Ratu Kidul or Queen of the South. Her presence was needed for the protection of the Mataram kingdom which, at that time, was threatened by outside forces. This place, the Cepuri, is the final location of a straight line that connects Mount Merapi to Titik Nol Jogja to Kraton Jogja to Panggung Krapyok, and finally Cepuri Parangkusumo to the sea.

I’ve learnt from this trip that man, nature and God are weaved through an indelible connection. Although the Javanese of Jogjakarta are Muslims, the presence of other worldly creatures is not denied and sometimes even revered by them. The Javanese are a proud people, who hold on to their traditions vehemently despite the change in powers that rule over them throughout the centuries. What remains staunchly believed by the Javanese is, that there are other beings that share this earth with humans, and contrary to the assertion of modernity that man can control nature, the Javanese people taught visitors like me that man must respect nature in order to live harmoniously with it.

My travel to Jogjakarta was organised by Jogja Jaya Trans Travel Agency which provides private transportation along with an English speaking guide. You may contact Wisnu if you’re interested in a custom made travel experience in Central to East Java at +62 813 285 28191. Mention code merizarose and get a special price from Jogja Jaya.

In The Beginning

“Your heart should adapt and be as good as normal.” With that, I was given...

Story: I hate you

“It’s time,” Danial proclaimed during our anniversary dinner. It had been a year since the...